Legacy of Queens and Kings

Queens of Kings

Move along Kings, now its the Queens time to shine, and into the Valley of the Queens we go.

Although only three or four tombs are currently open to visitors, the Valley of the Queens contains at least 75 tombs belonging to queens of the 19th and 20th Dynasties, as well as other royal family members, including princesses and Ramesside princes. The most famous is the Tomb of Nefertari, and the others include those of Titi, Khaemwaset, and Amunherkhepshef.

Nefertari’s tomb is often called the “Sistine Chapel of ancient Egypt” for its vibrant, detailed artwork, and it was meant to be one of the highlights of my trip. Until I found out it was closed.

This is where I get a little miffed about the lack of clear, up-to-date information when planning trips to places where such info isn’t exactly so readily available. So, consider this a bit of a PSA too.

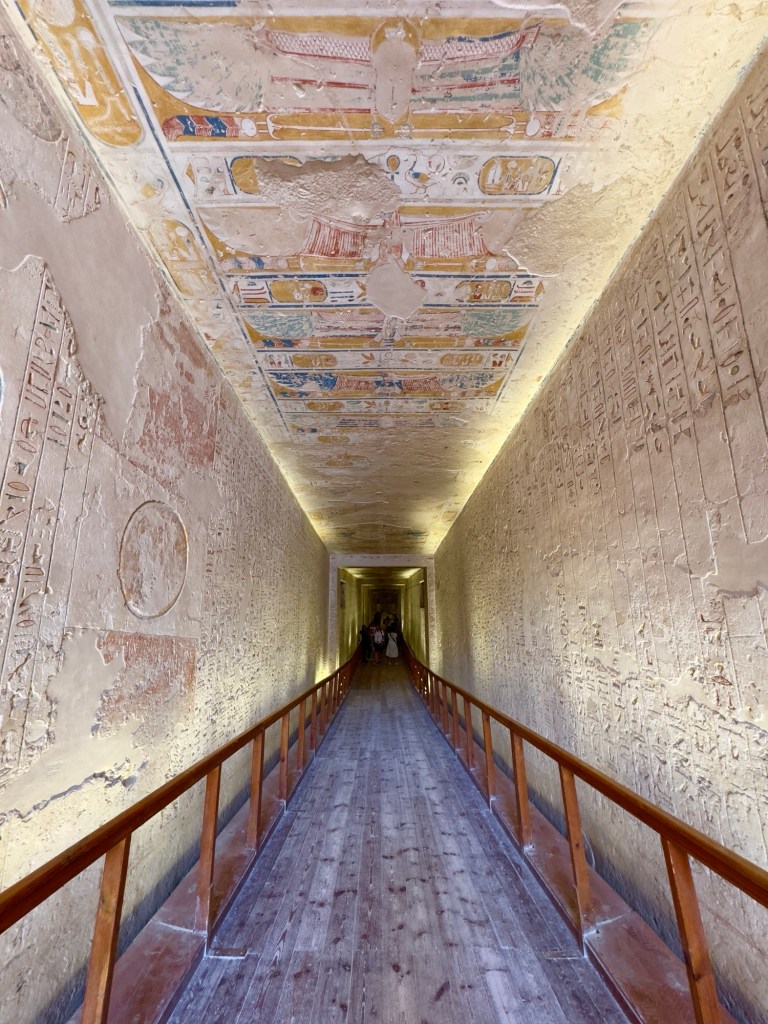

The Tomb of Nefertari is like Seti I’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings: expensive, expansive, impressive, and frequently closed. It’s not included in the Valley of the Queens general ticket (which covers the other three tombs) and requires a separate 2000 EGP ticket—for just 10 minutes inside.

It’s said to be one of the best-preserved historical sites in all of Egypt. Though relatively small—only three accessible chambers—the paintings are so pristine, they look like they were just finished. I was genuinely excited to see it.

At the time of my visit (January 2025), it was marked “Temporarily Closed” on Google Maps that morning, and when I arrived, the caretakers confirmed it had shut down just three days prior for urgent restoration. And honestly, I completely understand and appreciate how quickly they act at even the slightest signs of deterioration—even if it did rain a little on my parade.

What I don’t appreciate, though, is the black hole of information surrounding these closures. As I write this (April 2025), I’ve been periodically checking Google Maps, forums, and every other possible channel for updates over the past four months. And let me tell you—the closure schedule is as spontaneous as it gets.

Right now? “Temporarily Closed” again.

Five days ago? “Open during usual hours.”

Moral of the story? Be flexible i guess.

As much as you’re on holiday and have your heart set on certain sites, things happen. At least you know they’re doing what’s best for the preservation of these incredible monuments.

So rather than simmering in disappointment, i moved onto the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, and the word ‘impressive’ doesn’t even begin to cover it.

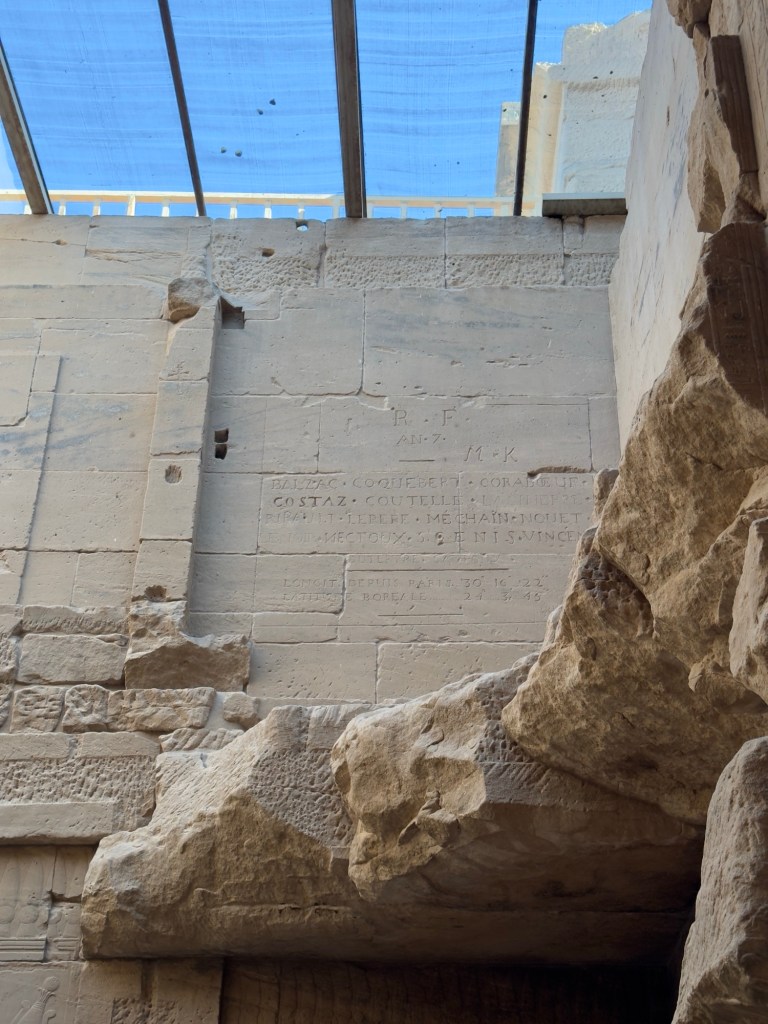

Legacy Etched In Stone

From the ticket office, you can already catch a slight glimpse of its grandeur in the distance, as rising up almost 30m from the desert floor, the Temple of Hatshepsut, also called Djeser-Djeseru (“Holy of Holies”), is one of ancient Egypt’s greatest architectural masterpieces. Commissioned by Queen Hatshepsut, Egypt’s most successful and my personal favorite female pharaoh, the tomb was designed by her royal architect Senmut.

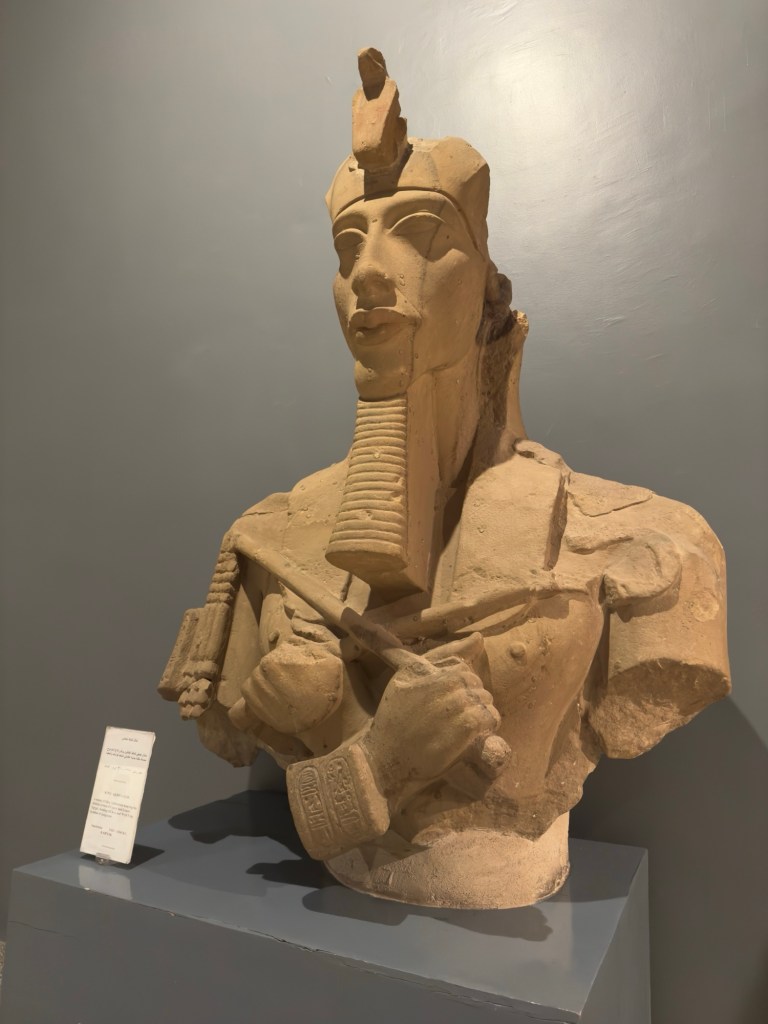

The temple is famous for its stunning, modern-looking design—three colossal terraces rising directly against a backdrop of towering limestone cliffs, almost as if it were carved straight of the rock cliffs themselves. And as with many monuments in Egypt, it wasn’t spared from the usual historical vandalism: Tuthmosis III removed his stepmother’s name whenever he could; Akhenaten removed all references to Amun; and the early Christians turned it into a monastery, you know, the usual stuff.

Wide ramps connect each terrace, and elegant colonnades frame reliefs that narrate her divine birth, expeditions to the rich land of Punt, and her unprecedented rule as a female king. The temple was not just a memorial for Hatshepsut, but a place to honor the gods, especially Amun-Ra, to whom it was primarily dedicated.

The terraces were originally lined with gardens and incense trees. Hatshepsut imported frankincense and myrrh from Punt (modern Eritrea/Somalia). Near the entrance, you can even spot a fenced-off stump from one of these ancient trees.

By the time I arrived, it was midday, and the crowds were out in full force. Pockets 360EGP lighter, I began what I can only describe as a pilgrimage. Not in the religious sense—though the sunlight bouncing off the white stone was so blinding I nearly found God(s). (Bring sunglasses. Seriously.)

The approach up the two ramps feels symbolic, like retracing the path of ancient priests—while simultaneously dodging modern-day tour groups and overly committed photographers.

Once at the top, the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari loom 300 something meters above the desert, forming a dramatic backdrop that amplifies the temple’s stature. On the third terrace, some of the 24 colossal Osiris statues still stand, leading to the Sanctuary of Amun. It’s modest compared to the outer temple—carved into the cliff, with minimal decoration—but still retains ancient pigments, especially the blue-painted starry ceiling.

Other than the main sanctuary of the temple, the best-preserved reliefs are on the middle terrace. On the north colonnade record Hatshepsut’s divine birth and at the end of it is the Chapel of Anubis, with well-preserved colorful reliefs of a disfigured Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III in the presence of Anubis, Ra-Horakhty and Hathor.

The Punt Colonnade to the left of the entrance tell the story of the expedition to the Land of Punt to collect myrrh trees needed for the incense used in temple ceremonies. There are depictions of the strange animals and exotic plants seen there, the foreign architecture and landscapes as well as the different-looking people. At the end of this colonnade is the Hathor Chapel, with two chambers both with Hathor-headed columns. Reliefs on the west wall show Hathor as a cow licking Hatshepsut’s hand, and the queen drinking from Hathor’s udder. On the north wall is a faded relief of Hatshepsut’s soldiers in naval dress in the goddess’ honor.

How did i know all this? Well, the blessing (and curse) of being surrounded by tour groups is that while they’re a navigational nightmare, their guides are loud enough that you can get a free tour just by existing near them.

Silver linings, mates. Silver linings.

Stories Written In Blood

Medinat Habu was the next stop.

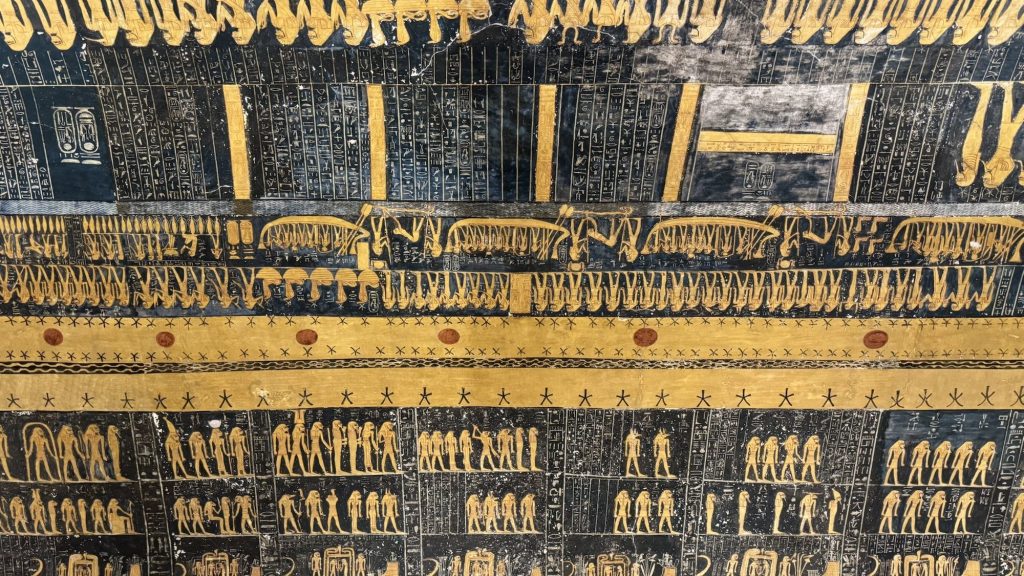

Originally built by Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III as the Temple of Amun, it was repurposed as the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III. The temple complex served as both a place of worship and a fortified administrative center during Ramses III’s reign, reflecting both his power and the turbulence of the time. The temple itself follows the traditional layout: monumental pylons, open courtyards, hypostyle halls, and an inner sanctuary.

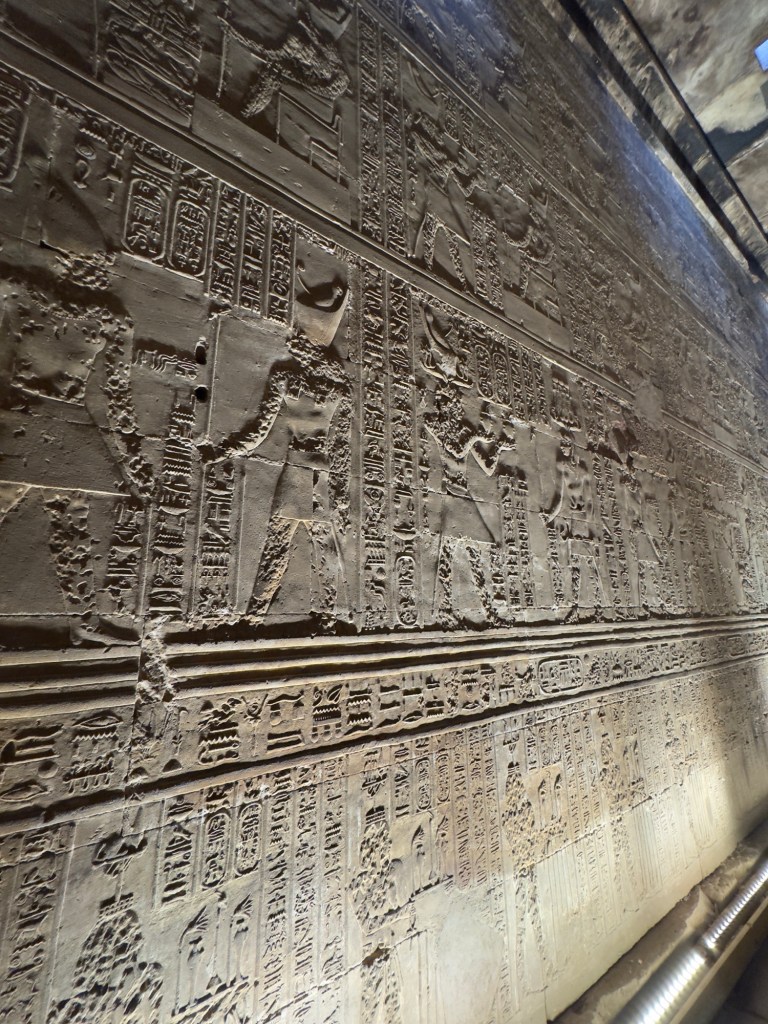

In my previous post i briefly described how Ramesses III tomb contained inscriptions depicting the tales of when he defended Egypt against the Sea Peoples, but here you can find that same story but fully blown out in stone carved upon the first pylon, adorned with dramatic scenes of Ramses III defeating the invaders whose defeat helped secure Egypt’s borders. One of the most striking and gruesome scenes shows rows of severed hands and genitals, counted as trophies from defeated enemies, a graphic representation of military triumph.

It served not just as his mortuary temple, but also as a political statement about Egypt’s strength and divine protection. Many of the reliefs still retain their original colors as well, a much needed reprise from shades of beige and brown, and offering a glimpse of how the carvings and art were colored back in the day,

Something i found personally quite fascinating about this temple is in its particularly deep carving style. The carvings are not just shallow reliefs like the ones that can be found in almost all the other temples, they are deeply incised into the stone, creating an almost three-dimensional effect that is particularly striking under the Egyptian sunlight, The deep carving style also made it more difficult for later rulers to erase or modify these depictions, contributing to their preservation. I believe this type of carvings are called sunk reliefs, according to one of the guides there, and are used more on exterior walls exposed to sunlight, whereas raised reliefs appears more often in interiors, allowing paint to adhere better.

Legacy left in Shambles

Last stop on my West Bank adventure: the Colossi of Memnon.

Not going to lie, i was expecting more. Don’t get me wrong, the sentinel statues of the Colossi of Memnon stands an impressive 18m tall, and were originally constructed to guard the entrance to Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. With such lofty descriptions scattered bout the interwebs you’d naturally have some vague but fairly glorified assumptions of what they would be like. But alas, reality is cruel.

The actual statues themselves are impressive yes, but its surroundings are unfortunately not. Situated smack in the middle of what seems like a dumping ground of stone and industrial waste, and literally surrounded by the commercial hustle and bustle of vendors who set up shop in the near vicinity selling their wares and trinkets, the semi derelict statues are perhaps the most well preserved items in the entire complex. The complex is supposedly ‘still undergoing’ excavation, but with the most recent report of it being from 2011 stating ‘halted due to lack of funds’, i do not foresee much work going to preserving these magnificent statues, as well upholding public order in the vicinity.

Entry into the space is free, there are no gates, checkpoints, nor tickets required to visit the statues, and security is lackluster, it kinda is everyone’s land there. Just getting in and out to snap a couple pictures felt like i just signed up for the Hunger Games dodging grabby hands and eager vendors instead of arrows and projectiles.

A sad state of things for the Colossi of Memnon, which is actually quite rich in history as the statues once flanked the entrance to what was one of the largest temples in ancient Egypt, after an earthquake, the northern statue began to emit mysterious whistling sounds, which the Greeks interpreted as the voice of the mythological hero Memnon, a hero of the Trojan War, giving the statues their famous name. Though the “singing” ceased after the Romans repaired it. It is only a shadow of its grand legacy, basically decimated with nothing but scraps and the two statues left.

What’s Next?

After a rather anti-climatic end to what was a breathtaking experience at the West Bank, it was time to recharge and reset once again, for it was going to be yet another long day to another two unmissable temples near Luxor – The Temple or Hathor at Dendera, and the Temple of Seti I at Abydos.